The critics on Young Mandela

Boston Globe – Kate Tuttle

Anyone who was in college in the 1980s remembers the songs, posters, and T-shirts urging divestment from South Africa and freedom for its most celebrated political prisoner, Nelson Mandela. Those who watched his inauguration in 1994 as the first democratically elected president in his country’s history will recall the feeling of triumphant joy. But Mandela’s story is more complicated than the happy, heroic narrative that has risen up around him. The elder statesman, now so respected for his peaceful perspective, was once a young revolutionary, a lawyer willing to go outside the law in search of justice. Mandela’s autobiography, “Long Walk To Freedom,’’ acquainted readers with the man’s warmth, humor, and integrity; in this book, David James Smith, a veteran journalist, aims to show us his anger, impatience, and ambivalence.

Much of the book centers on the early 1960s, a time when one African nation after another won independence after a century of colonial rule. In South Africa, the struggle was different than on the rest of the continent partly because so many whites had made the country their home. While blacks, Indians, and those known as “coloureds” sought equality at home, the push for national independence came from whites, who feared that the British Empire would soon press them to end apartheid. In 1960, Prime Minister Harold MacMillan told South Africans that “some aspects of your policies’’ conflicted with England’s “deep convictions about the political destinies of free men.’’

After the Sharpeville Massacre, in which white police killed 69 unarmed protesters, the government banned both the African National Congress, where Mandela was a rising star, and the Pan-Africanist Congress, a more militant group opposed to interracial cooperation. Unlike the PAC, which advocated radical action to secure an Africa for Africans, the ANC sought a South Africa that “belongs to all who live in it, black and white,’’ as stated in the 1955 Freedom Charter, a document Smith says was drafted by Rusty Bernstein, a white Communist ANC backer.

Mandela, who had been on trial for treason, went underground after he and his codefendants were acquitted. After decades of nonviolent protest, the ANC formed its armed wing, Umkhonto we Sizwe (“spear of the nation,’’ abbreviated as MK), in 1962 with Mandela at its head and a logo designed by yet another white Jewish communist. Ambivalence over the use of force and alliances with white communists is a constant thread in Smith’s book, and the two issues merged in the birth of MK. As Smith writes, once he was “[f]reed from the charge of promoting violence, Mandela was now free to promote violence.’’

When Mandela was captured and brought to trial in 1962, his appearance in court wearing traditional Thembu dress signified his evolution from the suit-wearing “black Englishman’’ he had been at college and in his early law practice to a modern-day warrior, willing to use whatever tools necessary to fight for his people and his country. During his imprisonment, his status only grew more heroic.

Smith writes that his goal was to “rescue the sainted Madiba [an honorary nickname] from the dry pages of history, to strip away the myth and create a fresh portrait of a rounded human being,’’ and for the most part he succeeds. He interviewed dozens of Mandela’s family and associates and comes up with some nice portraits of lesser-known players in South Africa’s political history, such as the white communist Jack Hodgson, who brought his wartime expertise in explosives to the early days of the MK. He unearthed the divorce complaint filed by Evelyn Mase, Mandela’s first wife, who accused him of beating her (accusations that, Smith points out, Mandela refuted categorically). And he interviewed many of the women with whom Mandela was rumored to have had affairs during the end of his first marriage, a time when, in an early unpublished work, Mandela wrote that he “led a thoroughly immoral life.’’ At the end of that period, he met Winnie Madikizela, a young social worker who would become his second wife and serve as his de facto representative during his long imprisonment.

The book presents a vivid picture of South Africa under apartheid, when, as Smith writes, “[t]o be a black African . . . was to negotiate an impossible minefield of petty offences that might land you in jail.’’ Yet during the 1950s and 1960s the country was stirring with the possibility of its destruction. Despite (or perhaps because of) the high stakes, the antiapartheid movement seemed to have had more than its share of parties, affairs, and sexual intrigue (as one participant told Smith, “you never knew what tomorrow held so you went out and had a marvelous bloody time’’).

At times the book feels hastily pulled together, its narrative sometimes ploddingly chronological, at other times confusingly scattered. Long passages detailing infighting among the revolutionaries can feel sluggish. And most readers would probably like more glossing of key figures and events. Worse, it feels as if Smith, in aiming to humanize a hero, goes too far in petty complaints, at one point chastising Mandela for using a line from Nehru, uncredited, in a speech. Yet overall the author’s admiration for his subject is clear. In the end, Mandela’s flaws only make him more fascinating, and his movement’s ambiguities and conflicts map the crooked, hard-fought road that every freedom struggle must travel.

NEWS AND EVENTS

Latest Articles

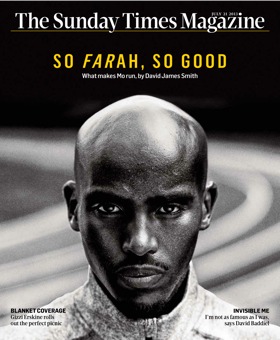

On the cover of The Sunday Times Magazine…

Latest News

The Sleep Of Reason – The James Bulger Case by David James Smith:

Faber Finds edition with new preface, available September 15th, 2011.Young Mandela the movie – in development.

From The Guardian

Read the articleIn the Diary column of The Independent, April 13th, 2011

More on my previously unsubstantiated claim that the writer-director Peter Kosminsky, creator of The Promise, is working on a drama about Nelson Mandela. I’ve now learnt that the project is a feature film, in development with Film 4, about the young Mandela. Kosminsky is currently at work on the script and, given the complaints about the anti-Jewish bias of The Promise, it is unlikely to be a standard bland portrait of the former South African president.

Latest Review

Nelson Mandela was circumcised as a 16-year-old boy alongside a flowing river in the Eastern Cape. The ceremony was similar to those of other Bantu peoples. An elder moved through the line making ring-like cuts, and foreskins fell away. The boys could not so much as blink; it was a rite of passage that took you beyond pain. read full review

See David James Smith…

Jon Venables: What Went Wrong

BBC 1, 10.35

Thursday, April 21st, 2011